Metropolitan Clubtalk #4: The tastemakers of the mixed city

In Metropolitan Clubtalk, a podcast series by TU Delft's Urban Design section, Robbert Jan van der Veen (TU Delft, ECHO Urban Design) talks to various guests about urban planning issues of today. Experts from government, education and design practice join in and share their insights and experiences on urbanism at all scales.

In this fourth and final episode: the city’s tastemakers. Kees Christiaanse (KCAP, ETH Zurich), Hilde Blank (BVR) and Maarten van Ham (TU Delft) discuss the challenges of the mixed city, in which not only housing, but also work and social programme find their place.

Ever since Cedric Prize drew the city as an egg, we have known: the city is like an egg. It is also how Kees Christiaanse, founder of KCAP and professor emeritus at ETH Zurich, explains the mixed city. ‘A fried egg has a yellow centre surrounded by a white patch. A scrambled egg is scrambled, but if you do that too much, everything becomes even.’ Area developments in challenging locations where housing merges with public functions, amenities and even industry are KCAP’s speciality. What we need is a more intelligent layout, he says. A city with diverse clusters with different identities. ‘Clusters of limited size, sometimes diverse, sometimes monofunctional due to regulations, are connected by good public space at strategic points. At nodes, meeting and exchange occurs.’ It conjures up an image even more colourful than a scrambled egg; the mixed city as a farmer’s omelette.

Inside out

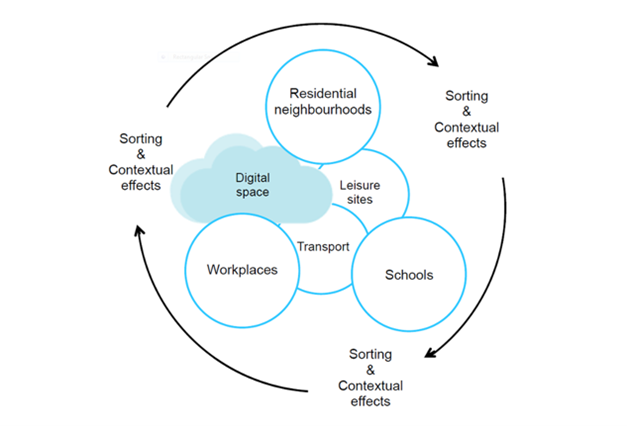

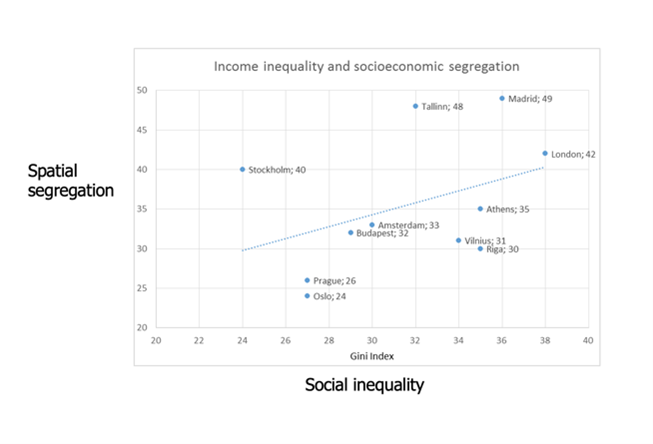

A city where living, working and social programme are intertwined does not come about by itself. This requires government control, the speakers say. The research of Maarten van Ham, professor of Urban Geography at TU Delft, shows that otherwise most money will simply end up in the best places. “There is increasing inequality all over the world. What we see is that this precipitates spatially; cities are becoming increasingly segregated.” Whereas the most expensive housing used to be on the outskirts of cities, now centres in particular are unaffordable. That turning the city inside out seems to be a universal process. The consequences of segregation can be enormous, Maarten says. Socio-economic groups meet less and less, do not have access to the same facilities and end up in the vicious circle of living in the same type of neighbourhood for generations.

“There is increasing inequality all over the world. What we see is that this is descending spatially; cities are becoming increasingly segregated.”

The non-residential programme also suffers from these dynamics. The pressure on housing construction is high and the space for additional building within cities is limited. When vacant building sites such as office parks, port areas or industrial sites suddenly offer space, housing is the first reflex. This does not always allow programmes that cannot pay the high rent to survive. The richness of functions that makes a city a city is under pressure.

Active control is the only thing that can counter this process, and for that vision is needed, argues Hilde Blank. As director of BVR, and as city architect and studio master at several provinces, municipalities and market parties, she works with diverse parties on the development of city and country. “Surely, we are a bit troubled by the past 13 years. A time when the government was almost not allowed to have a vision, not allowed to maintain coherence, had to be facilitative. Because of that focus on the market, you see that municipal departments have started to lag behind the developing parties and look at the city on a project-by-project, box-by-box basis.” In her experience, policy ambitions are sometimes applied without a view of what a place needs. “That’s how we lose our grip on cities.”

The city’s tastemakers

Yet there are plenty of examples of mixed-use area developments with guts. The redevelopment of the Santana Row shopping mall that Hilde supervised in the US drew lessons from Europe. “They were tired of all those indoor, air-conditioned spaces. Public space, they saw, is the key ingredient to making place. A good centre has meeting places for everyone. They also observed that people ultimately come because there is something that touches them. Tastemakers, who provide craziness, individuality.” It led to a pedestrianised area with open squares and streets in which giant trees were placed, and a system where social attractions are financially supported by commercial tenants. You can also steer this from quality teams, Hilde observes. “Look not only at architectural quality, but also at programming. How do you get it done that functions that may not always be commercially interesting still keep a place in the development?”

“Look not only at architectural quality, but also at programming. How do you get it to ensure that functions that may not always be commercially interesting still keep a place in the development?”

Blending is even more complicated when it comes to work. Industrial, hands-on work in particular brings vibrancy and bustle. Employees also like to live nearby. “Preferably 15 minutes one way,” says Maarten. But it is difficult to combine with other functions, and it takes up scarce urban space while housing is so necessary. In his own city of Zurich, Kees Christiaanse saw the SBB Werkstätte become the scene of this struggle. KCAP developed the master plan for this site of former railway workshops. On the one hand, there were calls for affordable housing, while on the other, a progressive city council saw the opportunity for a place with living, working and industrial activity. The smart compromise turned out to be to achieve maximum densification on top of the existing. A wide range of innovative and traditional industry has now settled in the halls; from bicycle makers to set workshops and coffee roasters. In the future, residential buildings will poke through this and give the area a silhouette towards the city. The Werkstätte will become a Werkstadt.

Key technology

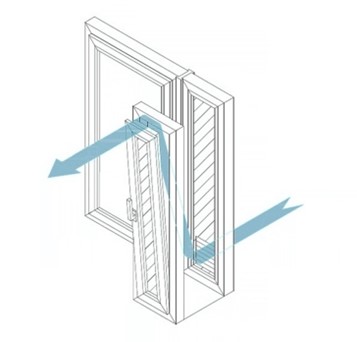

HafenCity in Hamburg is another such development, combining 50% housing with 50% urban functions such as creative industry and culture. Meanwhile, with the same ambitious development combination owned by the city, two new subareas are being taken up, Kees says. One will be an inner-city industrial estate, the other a combined port and residential area with even heavy industry. Innovative solutions such as a consolidation centre will make this possible. ‘An Asian term. Cities like Hong Kong are so densely built-up that no trucks can enter the neighbourhood. There, goods are transshipped at a distribution centre, from big trucks and rail cars to small electric vehicles and cargo bikes.’ Both districts arrange their logistics this way. And, all homes have the special ‘HafenCity window’. “Actually, we weren’t allowed to make residential buildings at all. But a clever acoustic engineer developed a window, a double window where the negatives are sound-insulating. On the inside you open one side, on the outside the other. The sound passes through a corridor in the window and is absorbed in the process.”

As simple as it seems, perhaps this is the pinnacle of thinking through the scales, a technical innovation that ultimately makes a whole new kind of city possible. Hilde, involved as a supervisor in the redevelopment of the Schieoevers, argues for just as much inventiveness in Delft: “The Netherlands is good at housing construction, but when converting an old industrial hall, for example, I sometimes see us really struggling.” “While here, at the university, we are at the place where all kinds of innovations are thought out. Let’s not only think it up, but also apply it. And show exactly here in Delft what we can do.”

Beyond the stamp

One recurring theme resonates through every episode of this podcast series; how big tasks sometimes risk getting lost in the translation into concrete projects. With a practice of “postage stamp urbanism”, in which smaller plots are developed by market parties, the larger perspective of the city in which connections are made, but contrasts are also allowed to exist, is no longer always sharp. It is up to both the government and the designer to think beyond boundaries to live up to the perspectives from this season’s four talks. A city as an attached whole, not as a collection of islands. Creating robust in-between spaces, not turned inwards, but as part of the urban fabric. Powerfully solving major transition tasks, not by lifting some tiles on every plot, but by choosing real interventions at the right locations. And making the mixed city, not by scrambling light yellow scrambled eggs everywhere, but by choosing characterful clusters in a colourful peasant omelette. This requires vision on all sides of the drawing board as well as ideas from unexpected quarters. Perhaps what you need is a HafenCity window.

This was the last episode of this season.